On the Oregon–Idaho border, near the little town of Nyssa, lies one of the most famous agate collecting sites in the Northwest: Graveyard Point. For over a century, this area has produced agates filled with striking “plumes” — delicate, featherlike inclusions of minerals that look almost like smoke or underwater plants frozen in stone.

The Setting

The Graveyard Point area is open, sagebrush country, cut by dirt roads and ranch land. Collecting usually means digging in claims or searching tailings piles left behind by earlier work. Some areas are under active claim today, so it’s important to know where you’re allowed to collect. A lot of people visit through fee-dig operations or purchase rough from local dealers who work the ground legally.

What You’ll Find

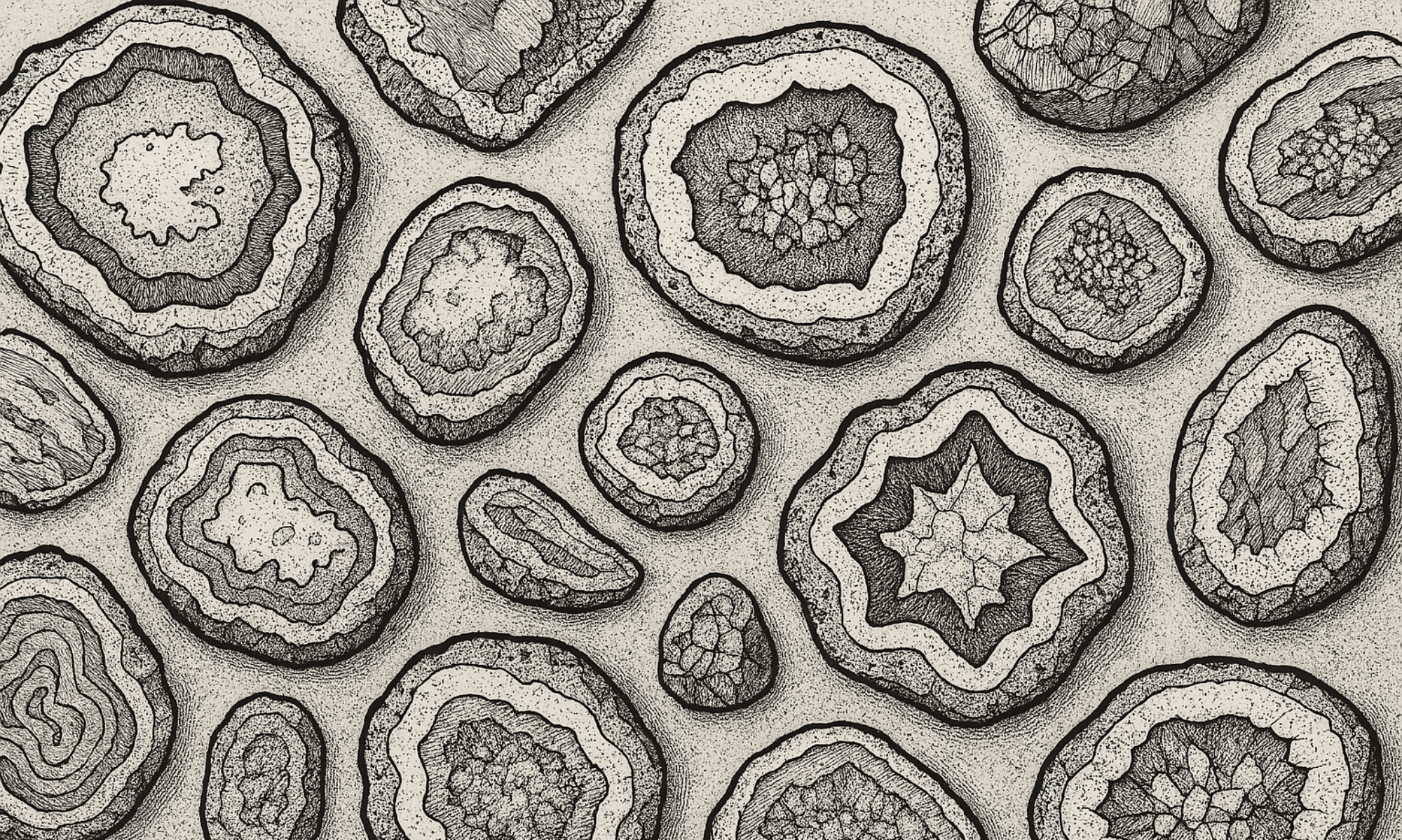

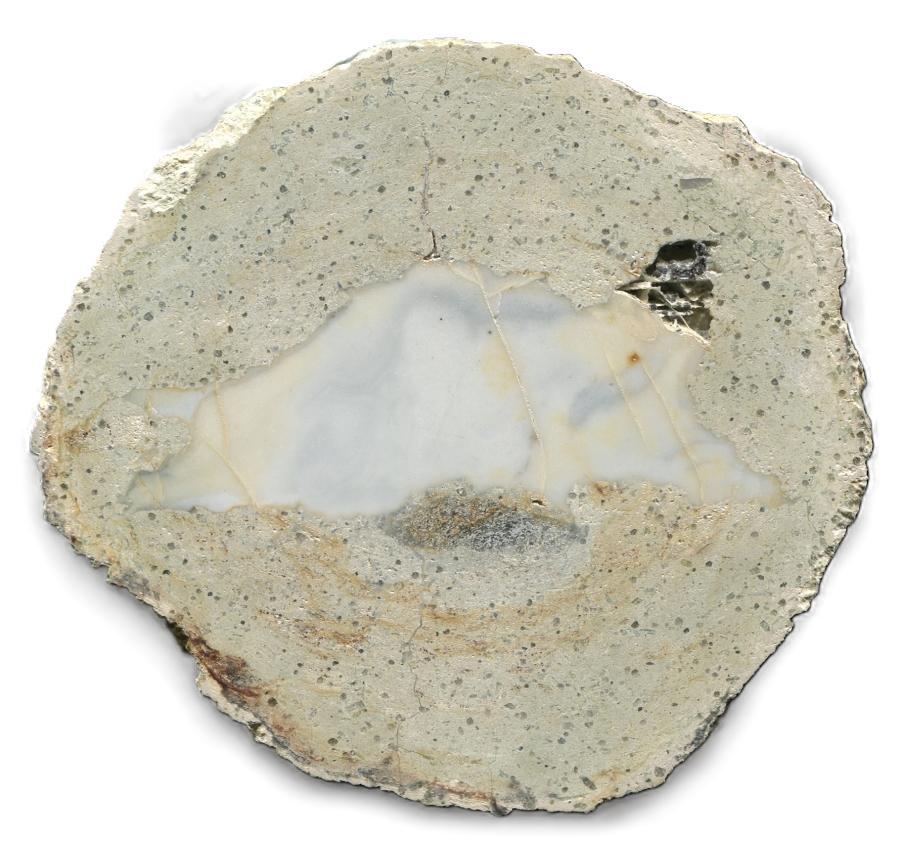

The agates here are known worldwide for their plumes. These inclusions can be yellow, brown, white, black, or even reddish, and they often appear suspended in clear or milky purple chalcedony. Good pieces polish beautifully and are prized by lapidary artists for cabochons and jewelry. The best material shows intricate branching plumes with strong contrast against the agate background.

The Collecting Experience

Digging for plume agate isn’t light work. Nodules and seams are buried in hard rock, so collectors often use picks, chisels, and sledges to break open the ground. Even then, not every piece is a keeper — just like with thundereggs or petrified wood, you’ll go through a lot of ordinary rock to find the special ones. Still, the chance of uncovering a piece of world-class plume agate keeps people coming back.

Why It’s Special

Graveyard Point has a reputation for producing some of the finest plume agate in the world. Many agate beds exist across the West, but few show the same level of clarity, pattern, and variety. The material has been collected and sold for decades, yet it still turns up in shows, shops, and private collections as some of the most desirable agate available.

Things to Keep in Mind

- Access: Much of the land is claimed or private. Always check before digging, or use fee digs where available.

- Tools: Strong hammers, chisels, and pry bars are often needed for serious collecting.

- Heat and dust: The desert setting means hot summers and dusty roads—bring water, sun protection, and plan for rough conditions.

- Buying rough: If you can’t or don’t want to dig, Graveyard Point plume is widely sold as rough or slabs at rock shows and online.

Closing Thoughts

Graveyard Point is more than just another collecting site. It’s a place with history, character, and a reputation that has spread far beyond the Northwest. For those who dig it themselves, the hard work makes a good find even sweeter. And for those who simply cut and polish the stone, the plumes inside speak for themselves — intricate, delicate, and timeless.